Structure of Equity

Jamaine Davis

Meharry Medical College

Published September 28, 2022

Numbers speak clearly to Jamaine Davis. As a boy growing up on Long Island, math came so easy to him that one of his family nicknames was "the professor."

Other numbers have shaped his ambitions at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, where Davis runs one of the few labs in the world that uses structural biology to help explain biological health disparities.

For example, U.S. Black adults are twice as likely to have Alzheimer's disease compared to non-Hispanic Whites. And despite a somewhat lower overall lifetime risk of breast cancer, Black women experience a 40% higher death rate from breast cancer than White women at every age and are more likely to be diagnosed with fast growing and late-stage breast cancer.

"My research program is basically at the intersection of structural biology, genetics and disease, and health disparities," says Davis of the big-picture questions that guide his lab's work. "What are the molecular mechanisms that dictate who develops diseases like cancer or Alzheimer's? And then how do we design effective therapies? How do we target the right pathways for the right treatment for that patient?"

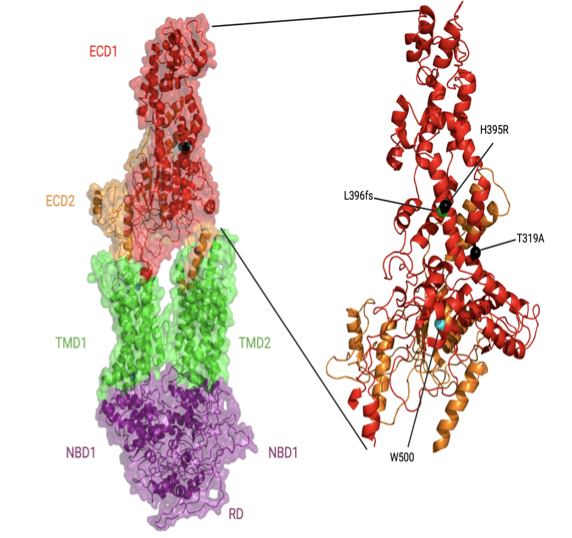

One project in the early stages focuses on a gene (ABACA7) that has a stronger effect on risk of Alzheimer's disease in Blacks than the better known ApoE4 gene risk variant. "It's actually the strongest risk factor for developing Alzheimer's in African Americans known so far," Davis says.

As he explains it, ABACA7 transports lipids out of cells, handing off the lipids directly to ApoE, and also interacts with Tau, another protein that goes awry in Alzheimer's. Two missense variants in ABACA7 confer the risk.

"So we've been studying these mutations to see what impact they have on lipid transport," Davis says. "Once we're done, we can look at the people who particularly carry this mutation or variant, see what downstream processes are altered, and design therapies to rescue that. And these variants so far have only been identified in African Americans."

Davis began his academic training on a different career path. With his early affinity for math and science, he reasoned that chemical engineering made sense as a college major. But near graduation at Drexel University, he realized that the typical next step for someone with a chemical engineering degree was a job at an oil company. He hadn't taken one biology course in college, but he found himself drawn to biomedical research instead.

He seized an opportunity to work in a biophysics lab at a neighboring school, University of Pennsylvania, where his mentor Jacqueline Tanaka gave him a peek at the scientific career he could have in biophysics and opened his eyes to the kind of academic role model he could be. Her excitement for X-ray crystallography and for increasing the proportion of women and minorities in science inspired him to go to graduate school.

"She built her career in structural biology and mentoring, hand in hand," Davis says. "She saw some potential in me, and I was at a crossroads." Davis had also been unaware of the extent of health inequities across the country and of the low representation of minorities in academia.

For his thesis, Davis chose the lab of Harvey Rubin, a dynamic speaker who fostered an immediate interest in infectious disease. In Rubin's lab, Davis characterized an enzyme that enables Mycobacterium tuberculosis to enter (and possibly exit) the dormancy stage in the lungs of people.

When Davis finished his PhD in 2007, he was the first Black to earn a doctorate in biochemistry and molecular biophysics at UPenn. "I had a great time," he says. "They were very supportive. But it is pretty shocking. If you look at Twitter, there are other people posting the same kind of statistic. They're the first Black to graduate from a certain program at a certain institution. It does show there is still some under-representation across different departments."

He followed up with two postdoctoral fellowships at the National Cancer Institute. He first showed that a novel protein in Shigella (bacteria that cause food poisoning) was not a protease, as some suspected. A second project elucidated the binding modes of a protein with multiple domain repeats implicated in the development of cancer.

Then he thought about how best to combine his interests in a distinctive research program. He chose Meharry, one of the oldest and largest historically black U.S. academic health centers. (Davis is also a member of the Vanderbilt University Center for Structural Biology.)

Historically black colleges and universities are powerhouses in educating African Americans who go on to earn doctoral degrees in science, technology, engineering, math, and medicine, as Davis and his co-authors reviewed in a commentary (Cell, 2022). Blacks make up 12% of the U.S. workforce, but only 5% of working physicians and 3.6% of full-time faculty conducting research at medical schools.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Davis found new opportunities for mentorship and community outreach. Soon after the pandemic took hold, a student-driven community formed on Twitter with the handle @BlackInBiophys and a logo designed by Taneisha Gillyard, a former postdoc in the Davis lab. Davis spoke at a virtual meeting held by the group.

In a short time, a strong sense of community developed among people who may have never met in person, but know a lot more about each other through social media, Davis says. People share grant writing tips, training and job opportunities, and generally celebrate the scientists, their contributions, and career options for the next generation.

The visibility may help change other statistics about Black researchers receiving less NIH funding and being cited less often than their white colleagues, Davis says.

Davis also teamed up with Meharry colleague Jennifer Cunningham-Erves to develop a funded community outreach project to address community concerns about vaccines. He has spoken about the basic science of mRNA at townhall-style community meetings, in person and virtual. The online recordings have reached people from Chicago to New York to Haiti.

The project collaborates with a consortium of more than 90 churches in middle Tennessee and Better Options TN, a community nonprofit organization. To understand concerns, the Meharry team interviewed people in the Southern United States. They developed and organized content on a frequently updated web site, https://yourcovidvaxfacts.com/en.

"We asked about their thoughts about the vaccine and the virus," Davis says. "The biggest one, particularly for Black Americans, was the distrust with government and healthcare. But I was very impressed with some of the questions that the public had. They weren't getting answers, and they wanted answers. If you remember, one of the major issues with people not getting a vaccine was that they thought it would affect their DNA. They just weren't familiar with mRNA."

Davis felt their concerns and trust issues as well. He initially was cautious about being vaccinated himself, waiting to see more data about its safety in people. "Even being a scientist, I was hesitant," he says. "I didn't want to be one of the first," he says. But as he explained the science and helped alleviate concerns of others, he also convinced himself to get the vaccine too.

Meanwhile, back in the lab after the pandemic disruptions, Davis and his team are working to improve health outcomes for populations most at risk, one variant protein and pathway at a time.

Carol Cruzon Morton