Drawn to the Light

Emina Stojković

Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago

Published July 30, 2025

Myxobacteria may be the most interesting microbes you've never heard of. That's what Emina Stojković realized when a summer student in her lab recounted vivid details from a recent microbiology class.

The best-studied myxobacteria were discovered growing on a pile of dry cow dung nearly 100 years ago. They cooperate in bacterial wolf packs to hunt other microbes, but they are non-pathogenic to people. They were first misidentified as slime molds, because in starvation conditions they form orange multicellular fruiting bodies that can be seen with the naked eye. Of potential medical interest, they naturally produce compounds with potential for antibiotic and anticancer drug design.

The more Stojković heard about myxobacteria, the more she liked.

Stojković studies light-sensing enzymes in bacteria. Specifically, she focuses on phytochromes, which detect light in the red and far-infrared spectrums and enable plants and photosynthetic bacteria to distinguish light from shade and adapt accordingly. Until her student raised the question, no one had thought to look for light-sensing proteins in myxobacteria. After all, they are not photosynthetic.

"These bacteria are so cool," says Stojković, who runs a lab at Northeastern Illinois University in Chicago now focused on photomorphogenic development of myxobacteria. "Because of my student, I switched to this system."

She soon identified interesting phytochromes in myxobacteria and secured the department's first grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to learn how phytochromes sense and signal the presence of light, and to what end, if not photosynthesis.

Training Grants: Terminated

The Stojković lab is fueled by students at Northeastern, primarily a teaching university. It advances the careers of bright undergraduates and masters' students as much as it explores new frontiers in photoreception and signaling.

Northeastern ranks as the state's most affordable public university, yet 97% of students receive financial aid. It's one of the most diverse Midwestern colleges and universities and a federally designated Hispanic-Serving Institution.

Stojković was hired with a mandate to grow research in the biology department, a mission she soon accomplished with a series of training grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) aimed at preparing low-income and underrepresented students for high caliber PhD programs.

But that all changed in April 2025. Stojkovic received three email notices from NIH in quick succession, each abruptly terminating two-existing and one-pending training grant.

The three ongoing grants had underwritten the research of numerous undergraduate students doing research in the Stojković lab and labs of her colleagues, as well as supported teaching and mentoring by three postdoctoral fellow mentors from nearby University of Chicago.

Training grant living stipends and necessary tuition support often allowed students to forgo parttime jobs, concentrate on research, build the skills needed to pursue a doctoral degree, and sometimes travel to a research facility to collect experiment data or to a workshop to present their findings. Most of her students were the first in their family to attend college.

The NIH cuts were part of the hundreds of millions of dollars of grants the agency has cancelled since President Donald Trump took office for a second term.

One grant-funded student was a refugee from Afghanistan now with US citizenship and on track to apply to medical school. She was the oldest English-speaking person in her household and sometimes brought her little sister into the lab. Another student was a US veteran of the war in Iraq.

"It's so heartbreaking," Stojković says. "If I could have five minutes with JD Vance and explain to him. He came from nothing, right? I don't think he would want these students to suffer, particularly a veteran like himself."

In the last 10 years, more than two dozen Northeastern students supported by the training grants have gone on to a graduate program at a major research university. And some of them are also feeling the pain of federal research budget cuts. She heard from a former student now in a PhD program at Harvard University whose NSF graduate fellowship had been similarly terminated.

Immigrant Background

Stojković was the first person in her family to pursue a career in science. She was born in former Yugoslavia, where she grew up and witnessed the horrors of civil war and economic sanctions on young people and education systems.

As a curious child, "I always had this urge to mix things and watch the colors change," she says. At one point, certain that something amazing would happen if she added salt, sugar and detergent to the soil, she inadvertently poisoned all her mother's potted plants on the balcony of their family apartment. She loved her math, chemistry, physics and English classes, often reading through all her textbooks before the term began.

In the early 1990s, when Stojković was a young teen, economic decline and rising ethnic and nationalist tensions ultimately led to the country's violent breakup and more than a decade of civil war. With the country under economic sanctions, her high school had no supplies for hands-on experiments. Instead, students reviewed the lab manual and designed experiments, and their teacher described likely color changes, smoke, odors and other outcomes.

To enable Stojković to pursue her scientific calling, her parents sent her to the United States on an exchange program for her senior year. She lived with a host family on Vashon Island in Puget Sound, Washington, where she graduated from high-school.

The next year, she attended St. Olaf College in Minnesota on a scholarship. She worked as a lab assistant and found meaning in the work and joy in mentoring other students. The lab also became a sanctuary as the situation in her home country deteriorated. There were times when she couldn't reach her family by phone. As an international student whose country was no longer recognized by the United States, she had to secure student visas from different countries.

"I was a student you literally had to kick out of the lab at night," she says. At graduation, her fellow chemistry majors voted her as most likely to discover a new element.

She sampled University of Chicago on a Howard Hughes Medical Institute summer research internship and returned to pursue her PhD in biochemistry. "I loved being in Hyde Park," she says. "It was so beautiful. And I loved this academic intensity of discovery, where you live and breathe science."

She stayed for a postdoctoral fellowship in structural biology. By the end of her postdoc, she had two young sons and a husband who had just finished his dissertation, so she accepted an offer from Northeastern Illinois to keep the family together in Chicago, the same year she received her green card.

Students and Collaborators

On her first visit to the Northeastern Illinois University (NEIU) campus in January 2008, she was struck by the diverse mix of ethnicities, nationalities, cultures and languages. It felt like a mini-United Nations.

The school did not grant PhDs, but Stojković was on board with plans to grow the biology research program. "I have always felt that sense of empowerment from science and the notion that science transformed my life, so I felt like I needed to use that to transform others," she says.

In her lab, she first carried on with her postdoctoral efforts to probe the shape-shifting details of how light-sensing proteins in photosynthetic bacteria respond biochemically to red and far infrared wavelengths. She switched to the myxobacteria at the suggestion of an undergraduate who had immigrated from Mexico and graduated with a perfect GPA from a nearby magnet high school rated among the best in the country.

With few resources at hand, Stojković recruited collaborators to supplement the expertise missing from her lab, boosted in part by connections she made at a Gordon Conference on protein photoreceptors in Italy in 2014 that she attended at the urging of her postdoctoral mentor Keith Moffat.

"I learned very early on that if I want to go from discovery to publication, I cannot do this by myself," she says. Her network of collaborators was critical in analyzing large data sets and helping her find computational alternatives. Eventually, more people heard her lab produced great crystals that diffracted well and contacted her.

"None of the research I do would have been possible without people I collaborate with at research-one universities," she says. "I really owe a lot to my collaborators, in particular Marius Schmidt from the physics department at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, who stayed with me through all these challenges and helped me support my students and exposed my students to research environments in their institutions.

Sensing the Light

As technology and techniques evolved, Stojković turned to time-resolved X-ray crystallography when X-ray free electron lasers (XFEL) to make molecular movies in real time as single phytochrome molecules in tiny crystal samples are excited by the light. Stojković also uses cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) to evaluate larger structural changes within the context of the intact, wild-type photoreceptor.

One graduate student Stojković took on a trip to the XFEL laser in Japan became the first author on a paper that described the core light-sensing component of the phytochrome and respective intermediates of its photocycle (Structure, 2021). That student, Melissa Carrillo, first in her family to pursue scientific career, earned PhD in Switzerland and currently works as a beamline scientist at Sector 17 at Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratories.

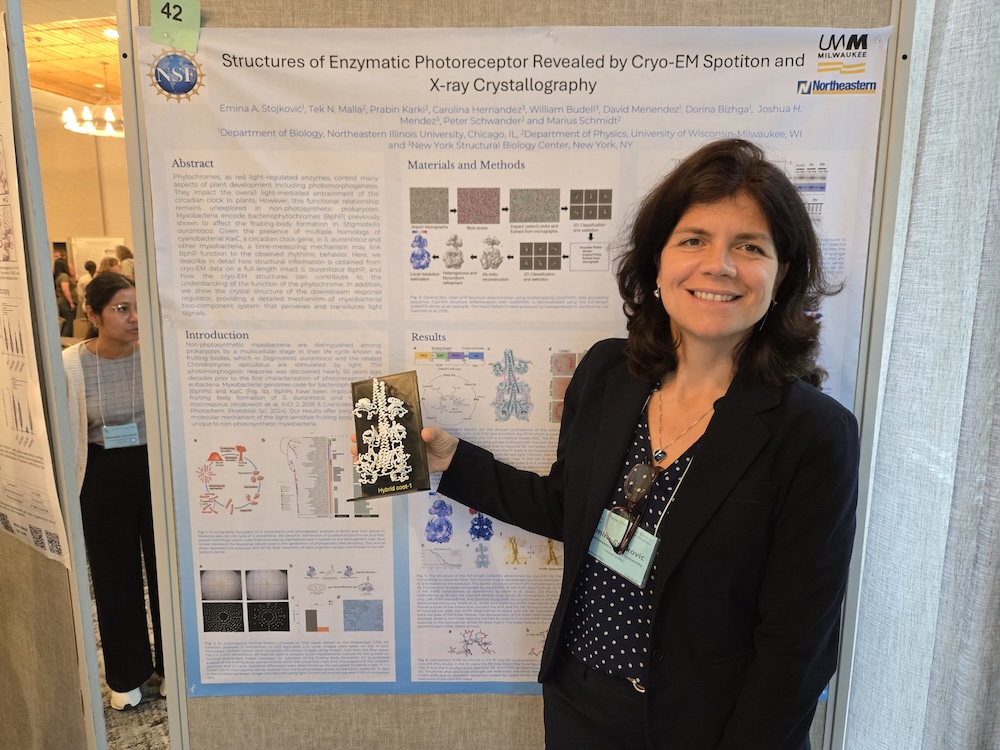

In a follow-up collaboration with the New York Structural Biology Center using cryo-EM, Stojković and her co-authors captured structures of the full phytochrome, complete with the enzymatic domain that connects to the signaling pathway, in this case a histidine kinase. (Science Advances, 2024).

The dormant protein is composed of two monomeric subunits that mirror each other, or a homodimer, but most of the images they collected show an asymmetric reaction to light, or a heterodimer. The results suggest that each half of the protein is activated sequentially.

"We can see the changes in the entire protein from the moment where the light is sensed, which is in this organic molecule that's brilliantly bound to the protein and gives it color, what we call chromophore, for the protein to absorb light, visible light, and we see changes in that chromophore and how those changes propagate all the way to the enzymatic domain," she says. "So you can see how light basically regulates the entire enzyme."

Future Uncertainties

The next scientific step is to solve the structure of the photoreceptor in complex with its kinase, a response regulator that ultimately triggers a physiological change in the bacteria.

As for the training program that undergirds the lab's work, Stojković feels grateful for the opportunities she has been able to give students and remains hopeful that new options will arise to support the next generation of students at Northeastern Illinois.

"I really take joy in the work students have done in my lab and the things they've learned," she says. "I have seen the transformational impact science can have on young lives."

In the meantime, Stojković is revisiting another goal that once helped her cope with the distress of being an international student from a war-torn country - training for a marathon. "Rather than losing my mind, I just started running," she says. "I ran and finished my first marathon as a senior in college with a t-shirt, signed by my classmates, calling for peace in my homeland."

This was the Twin Cities marathon on a Sunday. On Monday, when she walked into chemistry class, she saw a large display of the finishing times, with her name highlighted by her instrumental analysis professor, John Walters.

Now on the verge of becoming an empty-nester, she has her eye on the Chicago Marathon which she ran as a third-year graduate student. She can make time for a run about three days a week, on no particular schedule, as long as it's in the sunshine.

--- By Carol Cruzan Morton