The Stories Antibodies Tell

Jean-Philippe Julien

The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada

Published January 27, 2026

If only antibodies could speak! The tales they could tell. Their victories and defeats against viruses and parasites could provide a template for better protection against disease and death.

But scientists have ways of making antibodies talk.

With structural biology and other techniques, Jean-Philippe Julien and his team interrogate antibodies that arise from natural infections and vaccine trials. The secrets they have spilled already are shaping the design of the next generation of vaccines against some of the planet's most serious global health challenges.

High-level questions guiding his laboratory at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto, Canada, include: "What can they teach us about the vulnerabilities of these pathogens, and: How can we harness them to develop next generation of interventions?" he says.

"We believe that antibodies that see the actual pathogens have stories to tell," says Julien. "You can dissect the role of different parts of these pathogens by following the story of each antibody. That can guide design of interventions."

Antibodies have virtual eyes and ears everywhere blood travels through the body. As silent sentinels, the specialized Y-shaped molecules serve up a fluid archive of infections, vaccines, and exposures. Individually, one antibody may deftly grab one part of an invading pathogen, while another may not be able to hang on long enough to another part to immobilize the invader or rally immune cells to the defense. Together, they may map key molecular structures of complex pathogens better than scientists, especially for those that are hard to image directly in disease-causing conformations.

In a second major quest, Julien and his colleagues are asking, "how can we develop biomedical technologies to handle pathogenic diversity," referring to the infamous ability of many bacteria, parasites and viruses, such as influenza, to mutate frequently and render current vaccines less effective. "We see that as a very important unmet medical need," he says, "because pandemics and epidemics will continue to emerge."

Lessons for Malaria Vaccines

Both core themes in the lab converge on malaria, one of several infectious diseases under study. Nearly half of the human population is at risk for infection by the mosquito-borne parasite. The malaria toll increased slightly in 2024 to an estimated 282 million cases, mostly in Africa. Of the five most prevalent species, Julien works primarily on the one that causes the most deaths, Plasmodium falciparum. In 2024, 610,000 people died of malaria in 80 countries, mostly children under five.

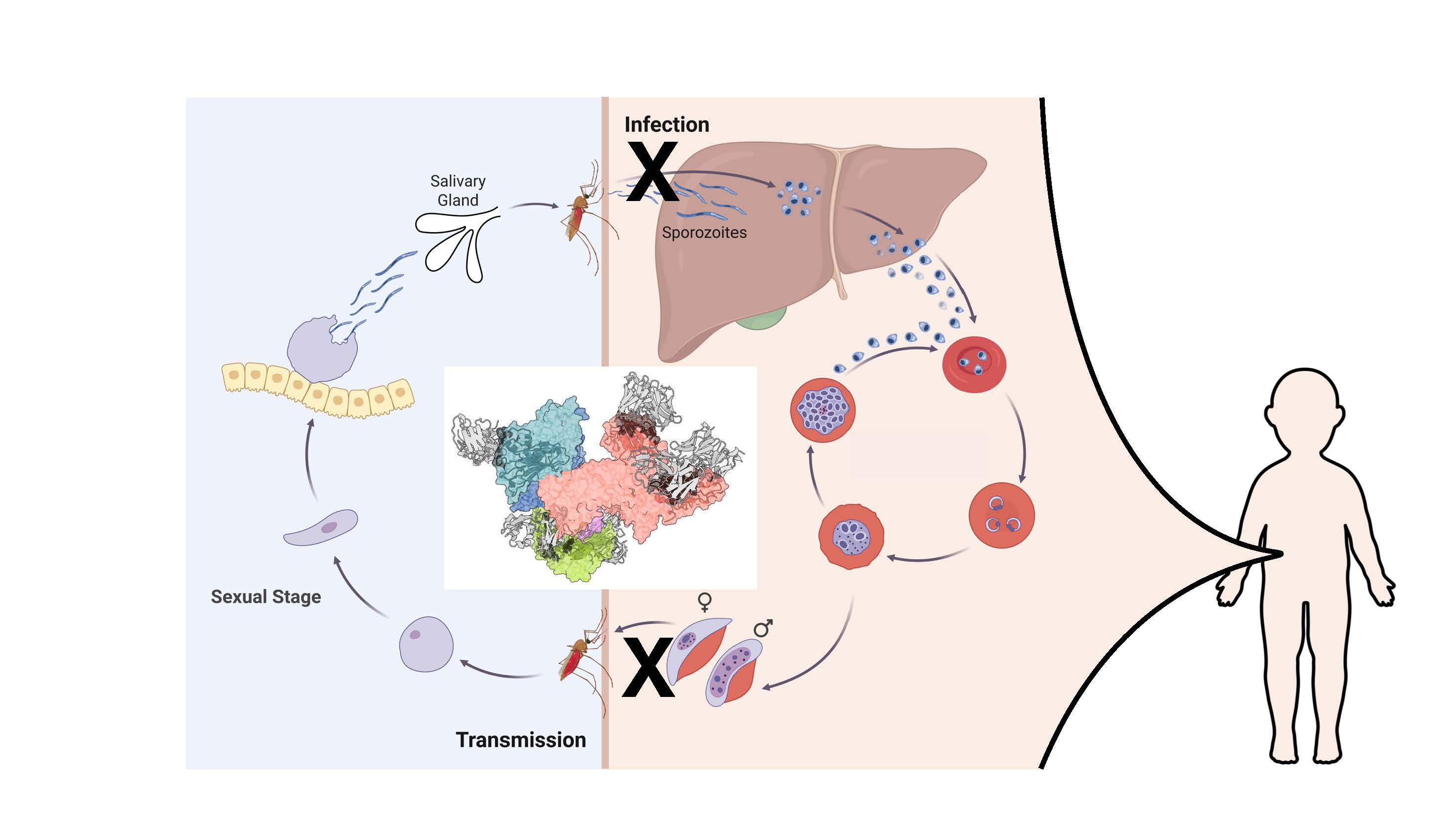

Malaria is a doozy of a vaccine puzzle. Infection by malaria parasites does not confer lifelong protection and only partially protects against future disease. The complex parasite lifecycle is an immunological thicket not well understood, but it goes through several stages. At each stage, the parasite's protein outer layer changes, helping it evade immune defenses.

In people, malaria begins with a bite by an infected mosquito. As the insect sucks in a person's blood, sporozoites race out and move from tissue to tissue in search of the liver. Blocking a single protein on the surface of sporozoites can prevent infection from taking place. But people do not develop antibodies naturally, because of the short window for the infection to reach the liver. "We're talking 15 to 90 minutes," Julien says.

Two recently approved vaccines now target the key surface protein, reducing cases by half in the first year after vaccination in studies. Julien and his collaborators have identified a different location on the same protein associated with higher antibody inhibition. In mouse studies, these elicited antibodies appear more potent than those prompted by existing vaccines. "We're hoping to test that in the clinic," he says.

At the next stage of infection, in liver cells, the parasite changes form and the proteins on the surface, then reproduces and reenters circulation with yet another set of proteins on its surface. It destroys some red blood cells and infects others. Human immune systems mount a vigorous response to the various versions, and people begin to show clinical symptoms that need immediate medical care.

In the red blood cells, the parasite goes through multiple stages of asexual reproduction, and some mature into exclusively male or female gametocytes with more limited proteins on their surfaces. A mosquito bite now will transmit the gametocytes back to the insect, where they will enter its gut, reproduce and make sporozoites to start the cycle over, propagating infections in humans.

The Transmission Bottleneck

Julien's lab is also working to block transmission from an infected person back to a mosquito. Adolescents and young adults can be asymptomatic carriers of the malaria parasite, and a mosquito could feed on them and then bite a baby or a toddler, transmitting the disease to youngsters who are more vulnerable to illness and death. "You would be saving the lives of these kids even though the intervention is not directly in the kids," he says.

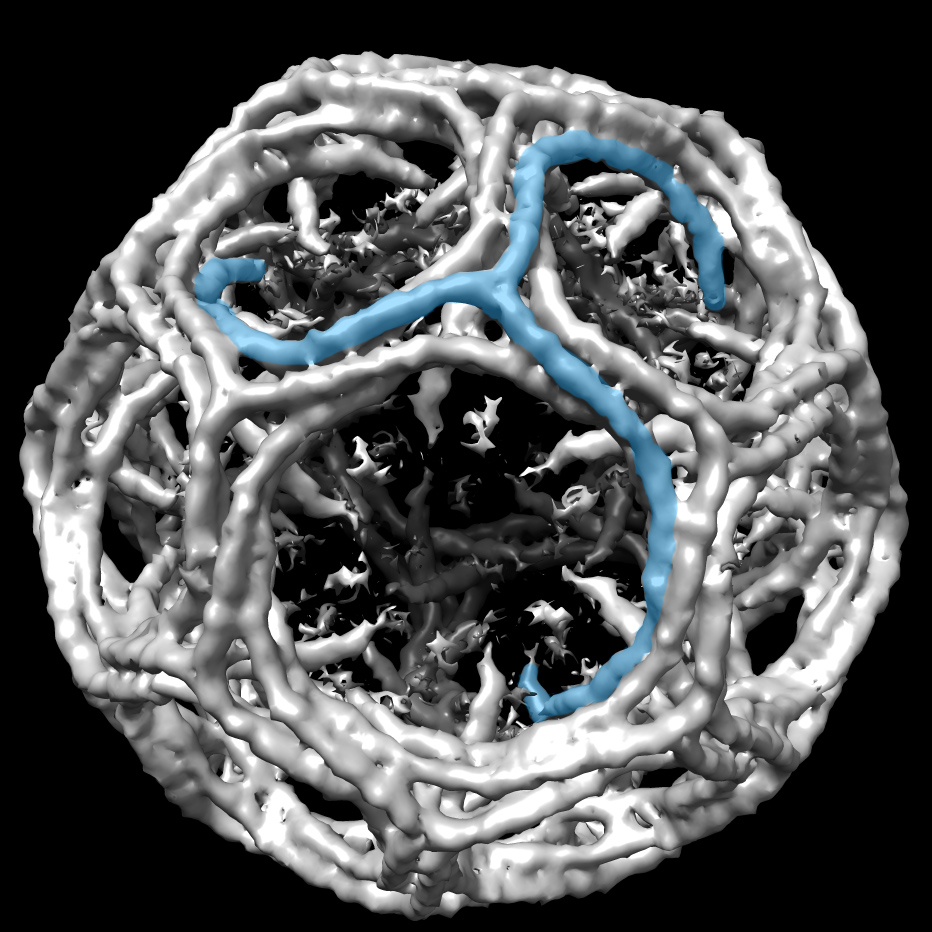

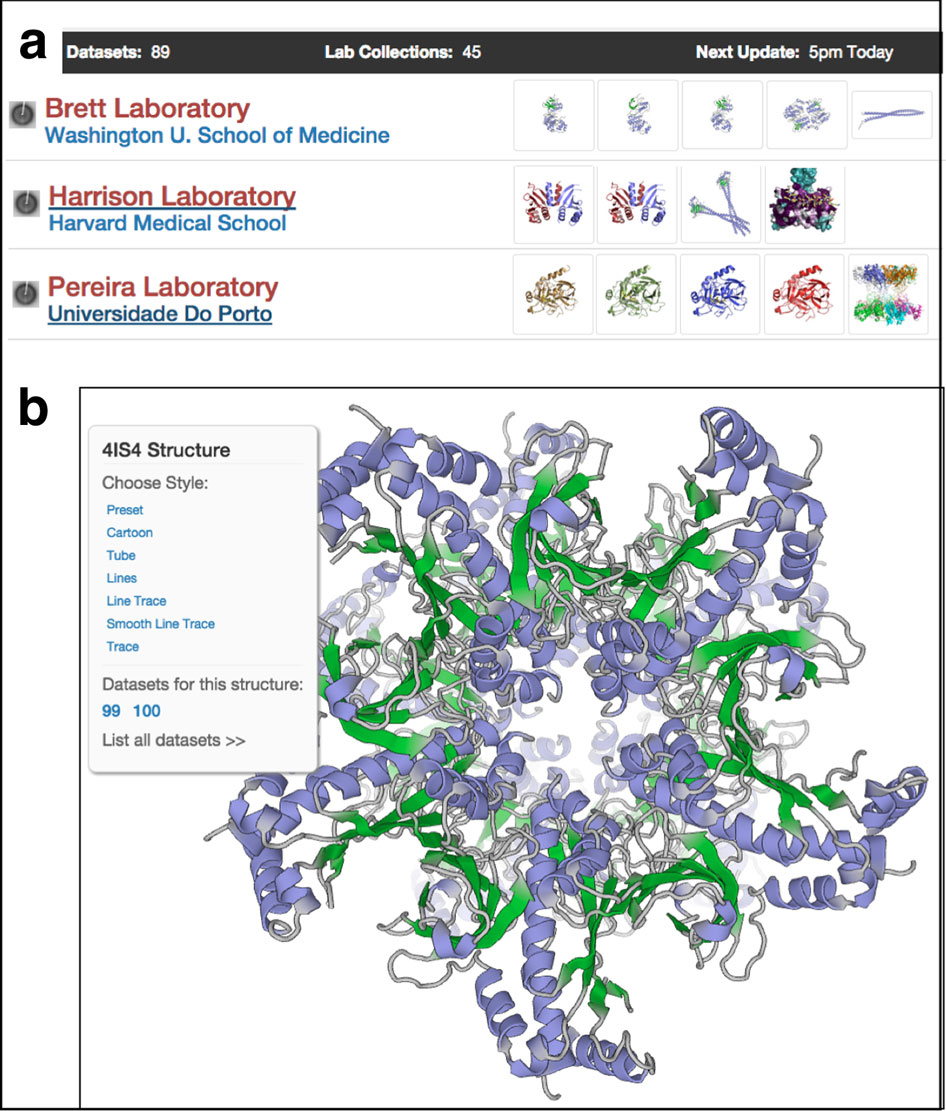

To block transmission, Julien's team ran their molecular analyses on gametocytes. With X-ray crystallization and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), they identified antibodies strongly bound to an established target of transmission-blocking vaccine candidates. One team described how antibodies pulled from natural infections in people were able to inhibit the parasite at the gametocyte stage. (Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, 2025). Another team characterized how the antibodies recognized the endogenous complex (Immunity, 2025).

The group is combining its efforts, aiming to transform the structural blueprints into a one molecule that blocks both the initial infection from the mosquito and the transmission back to the mosquito.

Ultimately, Julien and his colleagues are working toward a single molecule that targets all stages of the infection. In a large international collaboration, "each partner basically is providing one of these components, and then others are testing it in different pre-clinical models," he says.

Like other researchers, Julien and his collaborators lost some U.S.-based funding from the National Institutes of Health and USAID when the science and public health budgets were slashed. But "the community has rallied, and there's momentum for advancing the next generation of vaccines to have an impact for the kids and the broader population," he says. "Enough knowledge has accumulated over the last decade, and new tools have emerged recently in protein engineering."

Julien calls out one of his collaborators in particular. These mosquito mavens run an insectory at Radboud University Medical Center in the Netherlands. In the wild or in the lab, malaria parasites must be passaged through mosquitoes that feed on infected blood, allow the parasites to develop, and transmit back. It required months and months of culturing to obtain a few microliters for cryo-EM grids for Julien's team to image. "There are certainly a lot of clever approaches, but there is also brute force and sheer effort," he says.

For one of the recent papers examining the transmission-blocking antibodies bound to the target, the Dutch team "CRISPRed in a tag on one of the proteins of interest in the parasite itself, and then they grew billions of parasites," Julien says. "We were able to purify out that protein and solve the cryo-EM structure with six inhibitory antibodies bound to that complex. We hadn't known what the complex actually looked like. We just isolated it from the endogenous source, because recombinant technologies weren't allowing us to obtain that material."

The scientific journey

The science of global health was not an obvious career track where Julien grew up. His remote hometown of 20,000 in French-speaking Northern Quebec was the biggest outpost in a three-hour drive radius. The local economy was based on natural resources -- logging, hydroelectricity, and other ways of earning a living from the land. His parents worked in construction after some college, and his mom went on to complete her university degree and earn a master's in her 40s.

As a kid, Julien's interest was piqued by heartbreaking humanitarian problems far removed from his rural environment. In junior high school, Julien read news of a devastating earthquake halfway around the world and organized a fundraiser at the local school for victims.

He left his small town at age 17 to attend Pearson College at the southern tip of Vancouver Island with 200 other students from 80 or 90 countries. The boarding school is one of more than a dozen United World colleges on four continents and offers a two-year International Baccalaureate diploma. The underlying philosophy promotes peace through understanding cultures and peoples around the world. "Their mission is as important as ever," he says.

The school nurtured his global health interests and gave him an early sample of his future working environment -- the international culture of a research lab populated with a diverse array of nationalities and ideas, all working together to solve difficult problems. He sees the same sense of mission in people working in his lab now.

Julien returned to Quebec, where he majored in biochemistry and minored in social studies of medicine at McGill University. Small molecules and global health were an irresistible combination for him. He earned his PhD at the University of Toronto with Emil Pai, working on the structural characterization of an anti-HIV-1 broadly neutralizing antibody. He moved to San Diego for post-doctoral training with Ian Wilson at The Scripps Research Institute, focusing on functional and structural studies of the of HIV Env glycoprotein.

"The ability to screen antibodies functionally, to dissect which ones are beneficial or not, was very transformative for the field of HIV," he says. "We're now applying these techniques in other fields, like malaria, where we think they can be transformative."

By Carol Cruzan Morton