Stop, Collaborate and Listen

Eleanor Dodson

York Structural Biology Laboratory, UK

Published November 5, 2012

Back in the mid-1970s, the British government funded several collaborative computing projects. Among them (14 in all) was Collaborative Computing Project 4, known by structural biologists as CCP4. "The idea was that computers were so expensive, you'd probably only have one in London and maybe one in Manchester, so everybody would have to collaborate on using the hardware and developing software," says Eleanor Dodson, Professor Emeritus at the York Structural Biology Laboratory and a contributor to CCP4 from the beginning.

By then, Dodson had already been involved in structural biology for over a decade. With just a bachelor's degree, she began working in the lab of protein crystallography pioneer and Nobel Laureate Dorothy Hodgkin, who solved structures for penicillin, Vitamin B12 and insulin. "Dorothy needed a technician and I needed a job," says Dodson, who took on the work of hand-contouring electron density maps, despite her limited artistic talent. "I had great difficulty drawing a curve that joined up with its own tail," she laughs.

But what Dodson lacked in artistry, she more than made up for in mathematics. She had a hand in developing fundamental mathematical methods of crystallography, including molecular replacement, experimental phasing and refinement. "When there aren't hard and fast rules about how things are to be done, it's very great fun to be working in that field," says Dodson.

Though tedious at times, plotting curves on transparent tracing paper and stacking them up to make an image of a molecule taught Dodson the value of interdisciplinary collaboration. "Without that time spent on mundane chores, we'd have failed to appreciate the contributions of others," she says. "That's one of the dangers of today's quicker scientific results. You aren't as involved in the process and so you don't see how others contributed."

In the mid-70s, Dodson and her husband Guy Dodson, also a scientist, left Hodgkin's lab and moved to York. Hodgkin retired. The informal collaborations the software developers had formed began to dissolve. "We all realized how much we depended upon each other," recalls Dodson. "You need someone who will shout at you and say, look! That's a stupid result. You must have done something wrong!"

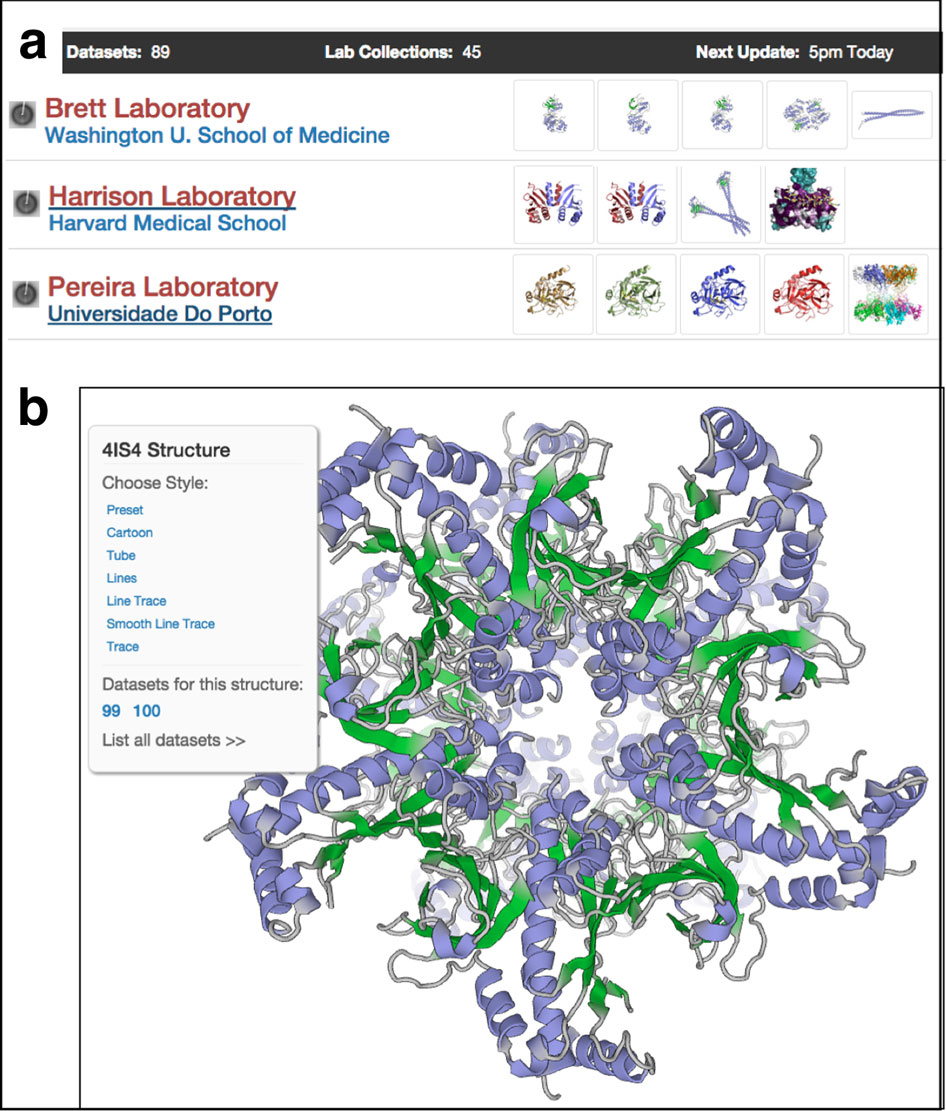

To reconnect, the group got funding for CCP4, and established a network of programs still used and maintained today. The effort established fundamental principles such as using centralized, well-tested libraries for common functions and standardized data formats. "We weren't aware that we were being innovative," says Dodson. "We were just practicing common sense."

Dodson continued to work within CCP4 throughout her career. A recent development is the program ACORN, (also freely available in CCP4), a phasing procedure for determining protein structures using atomic resolution data based on the ideas of the physicist Michael Woolfson, also at York. In 2009, Dodson and Woolfson demonstrated that the ACORN technique could be extended to solve structures with more limited data sets, providing the data was artificially extended -- using the so-called "free-lunch" approach.

Though Dodson has been a keen driver for more computer automation in structural biology, she has some concerns about the increasingly successful applications. "One of the disadvantages is that you're failing to educate the next generation of crystallographers," she says.

However, she continues, the many training workshops that have been funded by projects like CCP4 and, more recently, SBGrid, help counter this drawback by bringing people together to solve hard problems. "We try to solve such problems in several ways, to use different software, and to start from different points of view," she says. "They give the innovators of the future a chance to get their fingers in the pie."

-— Elizabeth Dougherty